Like most sane people, I have tried to ignore the writer known as Crumps since his modus operandi became clear. But at this point, at least in my circles, this strategy has become impossible. Which is just as well, because there are some important and surprising insights—about media, criticism, technology, and the literary arts—which you may gather from the saga of Crumps, once you look at it in the proper light.

Let me begin by paying Crumps a few compliments.

I have heard the criticism floating around that there is nothing to glean from Crumps’s writing. He is scene reporting, he is writing exclusively about frivolous parties, he is astroturfing internet beefs. He is, to sum up, squeezing the last drops from a fruit which is none too juicy in the first place.

This analysis is incorrect, for reasons I will explain below. In a limited sense, Crumps is publishing content with more insight and honesty than the average piece of criticism from legacy publications. On the other hand, his output also constitutes the apotheosis the most ignoble media trends of the last decade. I’ll discuss that toward the end of this piece. But for now let’s look at what Crumps has in his favor.

Crumps’s insight lies in his realization that the scene—which, for better or for worse, has of late come to be metonymized by the phrase Dimes Square (although the geographical location is not so important)—is one of the few places that feels artistically and intellectually alive. The reason for this is that this scene has broken at least partially free from the punitive culture of the last five to ten years which enforced callowness and stupidity on all media with astounding success. Crumps’s great insight has been to jump into this scene, which has real energy and vibrancy, and to write about it to the exclusion of all else. I predict that this will continue to be a successful strategy for him, and, insofar as he serves as an excellent publicist for those whom he purports to oppose, I wish him the best in his endeavors.

Crumps’s honesty is that in his recent pieces he is not so interested in ideas or in art. He is interested in people, and how they interact. In our highly pro-social, networked world, where hardly any work can exist independently from the reactions of those who see the work and share it with their own networks, this is a wise choice if one wishes to drive engagement. Crumps has stated that his style here is influenced by Dean Kissick, who cannily realized in his intelligent and entertaining Downward Spiral column that he could not write about art, especially not about net art, without writing about the cultural milieu around the artworks. And it is clear to anyone who has read both Dean’s column and the art criticism published in mainstream art reviews (the term itself feels anachronistic) such as Artforum, that Kissick’s writing about artistic milieus is far more interesting and incisive than legacy art writing, which uses a combination of bloated academic-ese and peppy marketing speak to describe artworks of minimal import at best.

Where Crumps’s insight and honesty ends is in his continued avowals that he writes in opposition to the scene he describes. This manifests as a reprisal of some of the more common and deleterious media techniques of the last decade—(1) seeking to drive engagement through cancellation attempts, (2) haterism (the drive to write about that which is compelling and controversial while enjoying the relative safety of feigning to despise it), and (3) what can only be described (though I’d prefer a more neutral term) as virtue signaling.

Let’s discuss each of three tactics, which have been mainstays of the last ten years of criticism’s descent into hysteria, starting with the much discussed but little understood phenomenon of cancelation.

Slander antedates the internet by a few millennia at least, but when one’s social network becomes the entire globe, this shift in quantity creates a phenomenon of an entirely new quality. Cancelation is actually a pro-social phenomenon. That is, it fosters community cohesion by demarcating what lines must not be crossed in order for one to remain within the community. The larger the community, and the stronger the pressures exerted by that community, the more forceful is the cancelation pressure. Today online we live in a community (not really a community, but it feels like one to our chimp brains) of billions. This has never been the case before, and it’s going to take a while for us to adjust to the extra strong cancellation pressures implied by that change.

Another phenomenon related to that of cancellation phenomenon is the glut of writing that serves as a means for participants to furtively engage with the content they putatively loathe—what I’ve termed haterism. One thinks of politicians who inveigh against sexual perversions, only later to be spotted making little gestures with their feet in bathroom stalls. The media version of this today is outwardly condemning “edgy” content because one is fascinated by it and condemnation is the only manner by which to engage with it. This phenomenon is easy to spot.

Our third topic is that of virtue signaling. For our purposes this consists of assuming a moral high ground without elaborating one’s own supposedly superior ethical orientation toward the world. I take it that Crumps has a vision, or at least a feeling, of supporting the downtrodden and living in harmony with his fellow man. This is a fine sentiment, but it is not exactly thought. For this sentiment to translate into critical intelligence, the possessor of the sentiment must explain precisely what their political vision is and how it could plausibly bring about the changes they wish to see. That’s where serious discussion begins.

***

Why bother outlining all this? As I wrote above, these three phenomena have been the mainstays of our media culture over the last five to seven years. But I find it obvious (and in this very limited sense, I may be more of Marxist than the leftists who see the political and cultural shifts of the last decade as the product of some kind of grassroots cultural movement) that these phenomena are primarily products of technological changes. The instinct to cancel, haterism, and virtue signaling all downstream from the pressures of a globally networked world. Cancellation is the best way to drive engagement (and engagement is what you need in the internet economy) without getting canceled yourself. Haterism is the only way to discuss potentially controversial content when you’re exposed to the judgment of a billion-person social group. And virtue signaling becomes paramount when this billion-person social group is perpetually exerting cancellation pressure on you.

These phenomena have decreased in intensity somewhat over the past year or two. Hardly anyone thinks this is a bad thing—at least not out loud. Enough madness has been witnessed that even those who might once have been aligned with these phenomena no longer wish to be associated with them. In conversations with writers, artists, and musicians, I’ve witnessed people breathing a sigh, as if to say “that’s over and done with; nature is healing.”

Not so fast. The pressures that brought us this sorry state of affairs is still there—only more so. The sclerotic old media institutions are continuing to bleed money as they compete for a billion distracted, dumbed-down consumers, and these institutions will have to demand greater and greater sacrifices of their contributors while promising lesser and lesser prizes. The world is becoming more online, not less. And if the means by which the world becomes more online are the centralized services that we’ve grown used to, these phenomena will become more powerful.

For those who care about a thriving world of arts and letters, the temptation to look toward the past must be (Slavoj Zizek voice) ruthlessly resisted. The temptation is always there to hope that things will blow over, and thus to be cowed by Crumps and others exerting cancellation pressure—with the thought in mind that if one can just get through this rough patch, the glory days of prosperous institutional media will return. They won’t.

Luckily, they don’t have to. The literary arts—fiction, poetry, criticism, perhaps even the occasional 10,000-word part report (if it’s a really good party)—will survive without legacy media institutions. But not because of mass consumption. The era in which literary criticism is driven by mass consumption is mostly over. When we try to push them forward we end up with the morass in which Crumps has found himself.

***

The Mars Review of Books, for which I serve as Editor in Chief, was founded to be an alternative to this type of stuff. I’m not naive enough to think that everyone wants to be high-minded all the time and discuss ideas rigorously and dispassionately; but I know some people do. And my aim is to provide a forum where those people can have it out. Obviously, this is not a project fully in line with market research. The market—when it comes to content, at least—wants blood.

And thus the market pressures writers to be more stupid and ad hominem than they really are. That’s what keeps the clicks coming. That’s certainly what keeps Crumps’s clicks coming.

Thus there are two paths forward for criticism. Let’s call them the Crumpsian path and the Martian path. The Crumpsian path is not only the three-headed monster of cancellation pressure, virtue signaling, and haterism; it is also the appeasement of these behaviors. Like Colonel Cathcart and Colonel Korn at the end of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, who agree to let the protagonist Yossarian cease flying missions and go home from the war, on the one condition that he agree to like them, Crumps and his ilk tacitly agree not to exert cancellation pressure on you so long as you appease the behavior and let them harass people other than you. It’s a bit like a mob shakedown. You pay up (with your dignity) or you suffer the consequences.

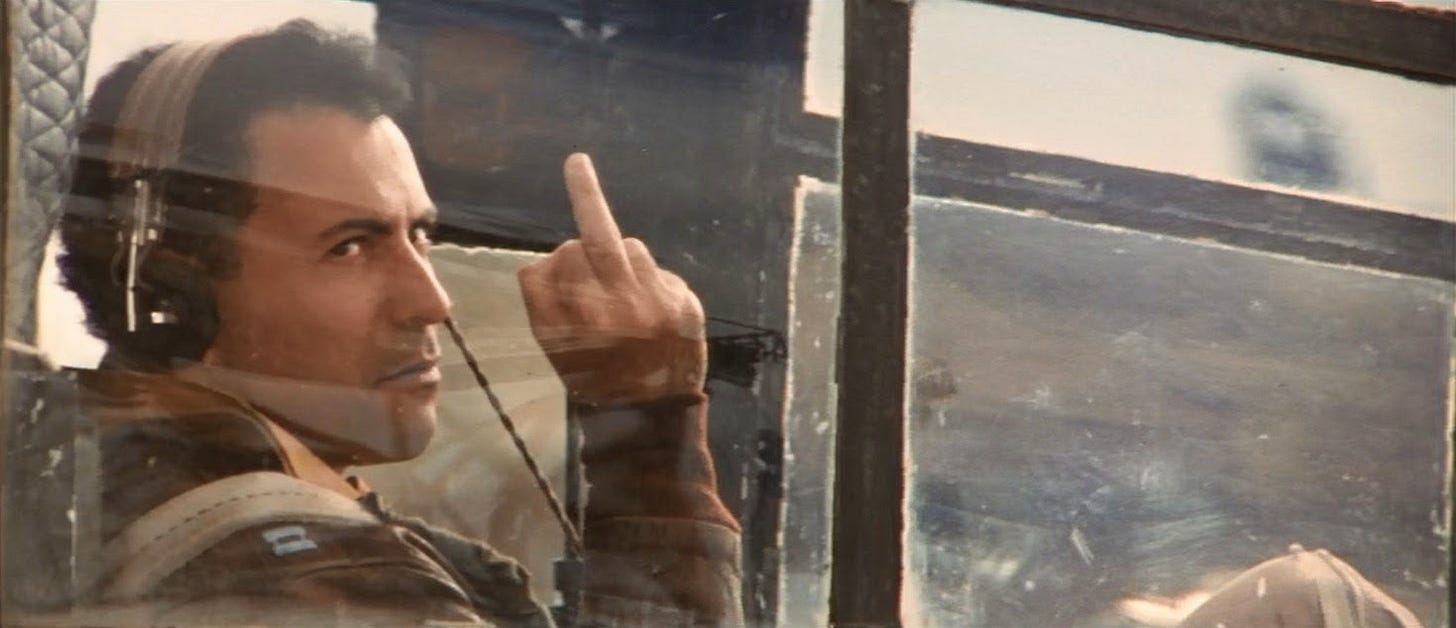

The Martian path is to cease striving to attract a billion shallow eyeballs, to ignore the threats of the Catchcarts and Korns of the world, and to exit the land of enforced homogeneity. To those who were brought up on the legacy system, this path can seem rather dark and harrowing. How does one get paid if Condé Nast isn’t writing the checks, and billion dollar Ivy League funds aren’t paying the grants? The answer will differ for every novitiate who treads down this path. But there are more opportunities than most realize—after all, it only takes “1,000 true fans” to give a writer a living. But these opportunities only open up fully as one develops the courage to flip off Cathcart and Korn, and to cease to fear ideas that diverge from global homogeneity.

Homogeneity breeds violence—whether it be verbal, or, past a certain threshold, physical. In a crowd full of people chasing status, as opposed to the truth, there’s little room for genuine distinction. Only certain people can be high status, and in a group where all are similar, the only way to settle the status question is through cliquishness and petty conflict. (This is why we see such rampant and deranged dogpiling in journalism, academia, and other fields where status games have taken the place of genuine inquiry.)

The way to avoid this hell is to help foster a world where heterogeneity exists. It is through heterogeneity that culture can move forward: If we allow ourselves to be cowed by the peddlers of homogeneity, then the results will be stagnation and petty violence. This heterogeneity will require small groups of writers more concerned with the truth than with status games, dispassionately publishing their ideas for thousands of serious readers rather than millions of callow ones. This is the Martian path. The choice is yours whether to follow it. I’ll simply say that the view’s pretty good from up here.

very good

Read your Calasso article then found this. Count me a new fan.