Ours is the age of inadequate Perennialist theory

Any other facts about this era are relatively unimportant, but I sometimes write posts about them anyway

A few weeks ago CNBC journalist David Faber interviewed Elon Musk on Twitter Spaces. The interview went as one might expect until the final question, to which Musk’s answer was unforeseen and fascinating. As a matter of fact, his answer touched on the most important theme in existence.

Faber mentioned that he had a college-age son, and he asked if Musk could give career advice for this son, considering the rapidity with which technologies such as Large Language Models (“A.I.”) are changing the landscape of white-collar work.

Musk said that advances in A.I. had made him question his own career choices. He recounted the “blood, sweat and tears” that he had put into his companies. And he wondered whether these efforts could be considered well spent, if it were to come to pass that machines will soon do all this work better than he could. In that case, he said, he would have been better off spending all that time with friends and family. He thus advised Faber’s son to simply follow whatever he was truly passionate about.

On the face of it, this is rather common—even banal—advice. But it contains the germ of something truly profound.

It appears to be the telos of machines to outstrip us at every activity that is not irreducibly human. The number of extroverted activities we partake in that are irreducibly human is becoming smaller by the day. It is well known that machines can play chess better than we can. They can also perform difficult manual labor than we can. It is now appearing that they can send work emails as well or better than we can.

What the machines cannot yet touch is the interiority of human experience. But even here, it is not exactly clear that they cannot do so. Materialist thinkers from David Hume to Freud have boldly claimed that our interiority isn’t really as sovereign as we like to think it is. For Hume and his followers, we are rather like machines ourselves, responding willy-nilly to external stimuli. If this is the case, it shouldn’t be so hard to build a machine that can simulate the human experience. And if human experience is truly just a response to stimuli, then what will be the difference between this simulation and the real thing?

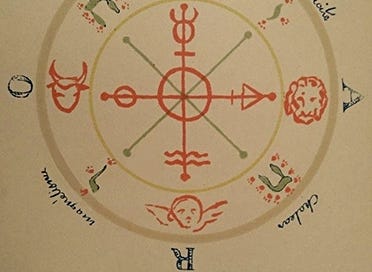

There is one internal experience, however, that remains unapproachable by machines. That is the religious experience. From the beginning of recorded history, people have called out such experiences as being the most important features of human life. And until the modern period, the religious experience constituted the the main experience around which human life was structured.

Granted, such experiences are often written about esoterically. In most cases, it’s hard to immediately understand what experience is being referred to. But what religious writers agree on is that religion is not something that can be reduced to a response to an external, material stimulus. (Religious experience does not admit, to borrow the phrase of philosopher Thomas Nagle, a psychophysical reductionist explanation.) The religious experience is something above or beyond our laws of physics.

We are in a very strange era with regard to the study of religion. On the one hand, brilliant scholars from the 19th and 20th centuries have made very persuasive cases for the unity of all religions. Writers as diverse as Helen Blavatsky, Julius Evola, Robert Graves, and Joseph Campbell have all advanced their different versions of this thesis. On the other hand, almost nobody seems interested in developing it further—although Jordan Peterson was making interesting movements in this direction several years back. But overall, the holistic study of religion has come to be dominated so thoroughly by the atheistic that those of truly religious character seem more inclined to retreat toward anti-ecumenical positions within their own sects.

Such a retreat seems to me impossible to justify on intellectual grounds. Textual scholarship has shown without a doubt the overlap in scripture in various religions. As I wrote about in Compact, the Christ myth is already extant in the ancient Sumerian corpus. In the Torah, the Genesis account of the world’s origin mirrors both the mysterious text of the Corpus Hermeticum and the Akkadian Enuma Elish. Both Achilles and Krishna die from an arrow to the heel. Can it really be argued that one of these religions is completely true, while the others are completely false? Meanwhile the world is being overtaken slowly but surely by atheism, and no single religion seems capable of rolling back this psychophysical reductionist offensive. With utmost respect for my firmly Catholic and firmly Eastern Orthodox friends—what could be the relevance today of, say, the filioque clause controversy?

From where I stand, there are two possibilities when it comes to religion. All religions are bunkum; or, all religions are permutations of a single truth from which they all spring. The former position , atheism, is the default ideology among polite, educated society. The name for the latter position is perennialism.

Which is correct? How can we even decide this problem?

We’re thrown back into the field of phenomenology—the study of consciousness and direct experience. To begin our inquiry, we can say something indisputable: Over the course of history there are untold numbers of people who have gone through experiences that they would describe as religious. They have experienced things which are indescribable in terms of the material world. These experiences at their peak tend to be life-changing, though not necessarily in a good way. The best catalog of such experiences that I know of is William James’s Varieties of Religious Experience.

We’re immediately faced, however, with a roadblock. A psychophysical reductionist would say: such experiences feel like religious experiences, but there isn’t anything to them beside the firing of neurons in an interesting pattern. A person undergoing a religious experience, in this telling, is rather like someone having a dream. It feels like you’re naked and have a physics exam that you haven’t studied for, but you aren’t actually.

This is a perfectly reasonable point. It’s also entirely indefensible. It is indefensible because it assumes a privileged position from which to observe the mental processes of others. One might just as easily say “you think you are having a rational discussion about the nature of religion, but you aren’t actually. You’re actually a brain in a vat or a character I’ve invented in my own mind.” If something that feels utterly real can be illusory, how do we know that all our other experiences are not also illusory?

We are, in, effect, back at the point Descartes started from when he conducted his thought experiments in Meditations on First Philosophy.

Descartes began his philosophical investigations by doubting everything, just as we are doubting everything when we say that the psychophysical reductionist’s cogitations are just as doubtful as the religious acolyte’s rapture. Descartes thought he got out of this mess by first identifying the cogito (Latin for ‘I think’). That is, he realized that whether he was being deceived or not, the mere fact that he was conscious was enough to prove that he did in fact exist. After all, something was happening within his mind. It would be obviously self-contradictory to think that he did not exist. Whatever is happening within his mind is happening, and that happening cannot equal nothing.

This is a very good point. But what if you were just a machine—an automaton without free will—which had been tricked into believing in yourself to be a free agent? In that case you might well exist, but only in a very limited way. And your religious experiences and rational arguments might be equally fake. Descartes anticipated this objection—calling it the “evil demon” hypothesis. “So I shall suppose,” he writes,

that some malicious, powerful, cunning demon has done all he can to deceive me—rather than this being done by God, who is supremely good and the source of truth. I shall think that the sky, the air, the earth, colours, shapes, sounds and all external things are merely dreams that the demon has contrived as traps for my judgment.

Today this idea is still popular. It is called simulation theory. Descartes went on, he believed, to refute it—although his supposed proof was controversial even at the time. We can, in any case, leave aside the the minutiae of Descartes’s argument. That is because Descartes made a larger error that we need to correct.

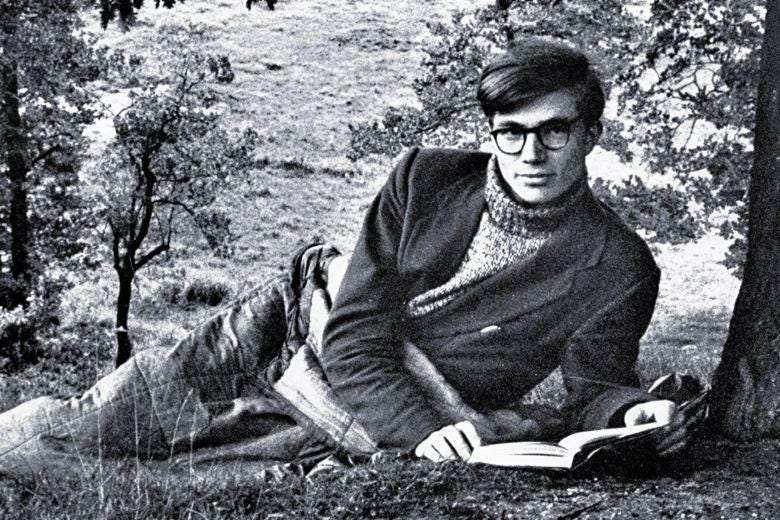

In fact Colin Wilson, the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, has pointed out that Descartes’s fatal mistake is one from which Western philosophy still has not recovered. Namely, Descartes tried to settle the matter of existence by passively observing his own consciousness. This is not the right route. The answer to our question about whether religious experiences are true or not can be found by noticing that consciousness is active, and the world changes based on our intentional conscious activity.

In his final book, Superconsciousness, Wilson mentions the poet Rupert Brooke. Brooke described his enjoyment of solitary walks with the phrase: “I suppose my occupation is being in love with the universe.” According to Wilson,

Brooke realized that he could bring on this feeling by looking at things in a certain way. And what was really happening when he did this was that he had somehow become aware that he could see more, become aware of more, by looking at things as if they possessed hidden depths of meaning. For it is true. He was becoming conscious of the intentional element in perception, that his ‘seeing’ was in itself a creative act.

For Brooke and for all others who are capable of intentionally altering their own states of consciousness, the objects of the world take on different forms at different times. In this case, we are asking an incoherent question when we ask if the world is real or an illusion. When we do so, it’s as though we’re asking whether the word being spoken in the famous viral auditory illusion clip is yanny or laurel. For some people it’s yanny, for some people it’s laurel, and for some (the scientists, let’s say) it is neither; it is merely a succession of sound waves. But whatever the case, the world cannot simply be something static for us to observe. It changes based on perspective.

What matters, then, is the quality of the “I” that is doing the perceiving. And not all Is are created equal. Descartes assumed that there was some canonical version of his self. But what if there are multiple versions? Think about it this way. Descartes’s philosophical descendants, such as Hume, take Descartes’s doubt one step further and believe that man’s sense of reality is simply a response to perceptual stimuli, which may or may not have correspondences to some objective real world. What we perceive to be reality is merely a collection of our own sense impressions. We are the authors of our own private universes. But if this is case, there’s one absolutely essential question that must be asked.

Namely, how did I create all of this world around me without knowing it? “[I]f ‘I’ really created the universe,” Wilson writes, why do I not know that I did? There must be two ‘me’s’, this everyday self who has no idea of what is going on, and another ‘me’ who is actually a kind of god who has created this world.”

To put it simply, there is more than one version of myself. One version of myself is able to observe the world around me, and one version of myself create the meaning behind things and form these perceptions into a whole. For instance, I can feel the complex emotion brought on by a symphony or recognize the elegant structure of a novel and be transported by that sensation. That is a different part of myself from that which perceives the notes of the symphony or reads the individual letters on a page. Both versions of myself are able to perceive something which is true—they’re simply different kinds of truth. It’s accurate to say that Anna Karenina is a series of abstract signs printed on paper and bound together. It’s also accurate to say that Anna Karenina is a perfectly structured and utterly moving microcosm of human life. Nor does this second ‘I’ which experiences meaning only come about by means of art. The psychologist Abraham Maslow identified that the common trait of so-called “healthy” people is that they regularly undergo what he calls “Peak Experiences”; that is, “a moment of awe, ecstasy, or sudden insight into life as a powerful unity transcending space, time, and the self.” This can come about simply from feeling grateful for family or from walking in the woods on a beautiful day.

We can say confidently that such experiences are true. Why? Anything we experience can be described as true from the phenomenological standpoint we’ve outlined above; but a peak experience or religious experience simply contains more experience. It is something deeper and more holistic. As William James puts it in his conclusion to Varieties of Religious Experience, someone undergoing such an experience

becomes conscious that this higher part [of himself] is coterminous and continuous with a MORE of the same quality, which is operative in the universe outside of him, and which he can keep in working touch with, and in a fashion get on board of and save himself when all his lower being has gone to pieces in the wreck.

In light of such experiences, our mundane experience of the material world is only a view of the world “through a glass darkly.” It is real, it is there, but experientially we know that it is not the whole of the thing, and we know that the whole, by being whole, is greater and more real.

It may be objected that this paradigm leads to a hopeless subjectivism. If the prime determinant of the reality of a statement is man’s experience of it, then doesn’t that leave us with a mess in which there is no baseline reality, and everyone is free to make up their descriptions of reality—all contradicting one another?

In short, yes—but this is actually no different from the psychophysical reductionist paradigm of any scientifically minded person. Just watch any criminal trial or pick-up basketball game to see the way that different people will give different interpretations of simple, concrete, observable events. One might counter that with proper scientific precision we could iron out such differences of opinion. And yet all around us, minutely observed ‘scientific facts’ seem to be at loggerheads with one another. Light or a particle? Unprecedented deadly virus or bad case of the flu?

Of course we are able to observe certain facts and make great predictions with them; this is what allows us to make our extraordinarily complex technological society work. But this is not the same as saying that each individual fully understands each element of an occurrence from the ground up and concurs with his peers about each of these elements. It’s more like two teammates playing well together in a game of Spades. Each has incomplete information, but each also has enough information to help his teammate succeed. For the most part, we live like dogs. We have no idea what’s actually going on around us, but when we follow simple instructions—sit, heel, put new cover sheets on the TPS reports—we are more or less in harmony with our peers, and things more or less work out. Things only go awry—magnificently, thrillingly awry—when we begin to think for ourselves.

Now with our background in phenomenology we can say confidently that religious experience is true, it is universal across all cultures, and is, according to both history and immediate human experience, the most important thing in the universe. What a pity that no one thinks to examine it seriously. In my next posts I’ll begin to do so.