Why I Am Not a Luddite

How Technology Destroyed the "Romantic Lie" of Modernity

I traveled to Mallorca last week, and, for the first time ever when traveling internationally, I didn’t miss a beat. Usually traveling to a new country it has meant, at the very least, no cell phone reception. Which turns out to be fine—I just get to the phone once I’m back home and respond to people. But now I had Google Fi International, and so even among the wild olive and lemon trees, on the most secluded trails and goat roads across this mysterious ancient island, I was responding to Signal group chats, playing into Twitter beefs, entering my Confirmation Number on janky airline app UXs. I had planned to be working while I was here, not vacationing, so this was expected. But it did feel rather odd.

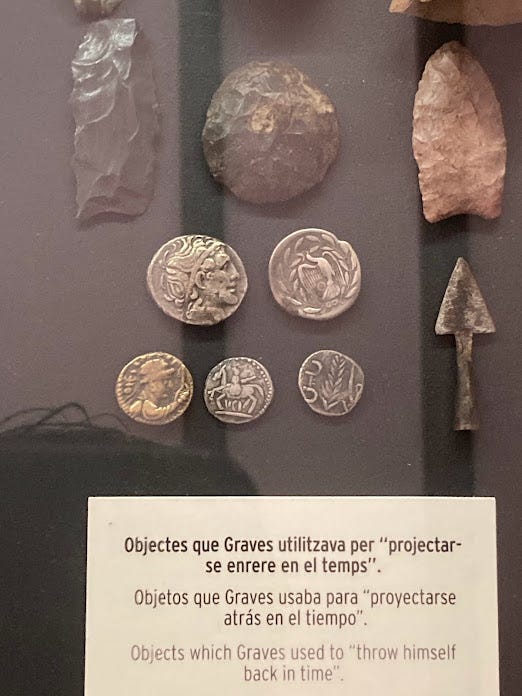

Then on the last leg of my trip, in Lisbon, I left my phone in an Uber. I think I had been disoriented when, right before I was to exit, my driver growled at me, “Five Stars. Make it five stars!” (Joke’s on him, I can’t log in to Uber now.) Just the night before in the remote town of Pollensa, a very kind gentleman (and a very good cook) from Staten Island had offered me a free bottle of water and a free beer (I declined), before asking me to give his Indian restaurant a good review on Yelp or Google. I of course obliged, and will repeat here that Singh’s place Om has to be the absolute best Indian food in Northeast Mallorca. On the big screen in Singh’s restaurant I watched endless YouTube videos of the late Indian rap star Sidhu Moose Wala. “He’s very popular,” Singh told me, “because he’d dead now. He was killed in India. He rose too fast.” Elsewhere on the island gung-ho Germans navigated rocky cliffs using AllTrails, my friend tracked his cycling stats with Strava, and I tried to manage Mars Review print subscriptions from atop the same cliff in Deià where the poet Robert Graves discovered the White Goddess who has for millennia presided over the ritual of poetic trance.

Then when I lost the phone, my feeling was something like ecstasy. It helped that I had got out of the cab just outside Lisbon’s National Museum of Ancient Art. I roamed the empty halls completely free. And yet my subconscious was starved for the infinite scroll. I looked at the paintings as though they were a feed. And the artists came to seem to me exactly like the best Twitter poasters of today. They’re all talented, and they’ve all got more or less the material (in the case of the painters, Christian and Pagan myths; in the case of poasters today, current events and scene gossip). So they’re trying to distinguish themselves any way they can. Some painters do so with weird individualistic flourishes, some with sexed up female subjects, some with painstaking attention to detail. The painters themselves seemed very mundane. And to me this made their work all the more glorious.

I first got into the software project Urbit through my luddism. I had felt that our technological advances were not only outstripping our ability integrate them into our lives but to even describe them properly; and so even carefully considered opposition was not technically possible. I later came to learn that this is an idea encapsulated by the term accelerationism. Because at the time it was not a problem that I could formulate very well abstractly, I wrote a novel about it in order to formulate it concretely. What began as a rather anti-technology book ended up as something of an accelerationist thriller. (Lionel Trilling has made the lovely observation that what makes the novel unique as a form is its capacity for staging how ideas play out in real life.)

Since then I’ve realized something a little more mundane about the reasons I felt so negatively affected by technology and especially social media. Namely, it stripped away any Romantic notions I had about myself. I use the term Romantic here in a very precise way. To quote W. H. Auden, from his introduction to my handy The Portable Romantic Poets:

Toward the end of the eighteenth century—Rousseau is one of the first symptoms—a new answer [to age-old question of God and man] appears. The divine element in man is now held to be neither power nor free will nor reason, but self-consciousness. Like God and unlike the rest of nature, man can say “I”: his ego stands over against his self, which to the ego is a part of nature. . . . If self-awareness and the power to conceive of possibility is the divine element in man, then the hero whom the poet must celebrate is himself, for the only consciousness accessible to him is his own.

I’ll give my own summary: With a Romantic view of life, one interprets the divine as a function of his own subjectivity. The intellectual dead-ends and grave emotional dangers of such a view are chronicled in the British novelist and philosopher Colin Wilson’s justly beloved book The Outsider. And in fact, Wilson wrote another 100 or so books examining the central problem of the Romantics: Why is it that they would get so high (experience the divine), before falling so low (“Ode to Dejection,” etc.)? Wasn’t there some way of accessing that divine rapture all the time?

Part of the problem with the Romantics is that they had Main Character Syndrome. They made a mistake no ancient would make: They forgot that they were mere vessels of the divine rather than generators of it. Eventually the Romantic became the Modernist and it became standard to assume that the artist’s subjectivity was an especially important part of his artistry; that is, he had a special perspective on the world that made his views particularly interesting and his art particularly numinous.

But, like the apocalypse, technology reveals how alike we all are—even these supposedly unique artists. For some reason I found it particularly shocking when I observed serious novelists all engagement-farming on Twitter with the same rote “resistance” tweets during 2016–2020; I assumed that they would have found it to be beneath them. But then I realized that they did not have any particular immunization toward group psychology simply because they were artists. In fact, they might even be more prone to giving in to it because they are trained to intuit what the reader wants from them. And in this case, the reader was continually delighted by “Orange Man Bad.”

To see that the human race is more or less programmable is on the one hand a very grim insight. It makes us look very small and pitiable. It shows us that the rationality we have valued so deeply in ourselves since the Enlightenment is at best a confidence trick. And in the end it’s rather frightening, as it shows the levels of absurdity and brutality to which all of us can be swayed with simple appeals to authority.

It may also be the most beautiful and momentous insight to occur in several generations.

Why so? It goes back to Romanticism and what we might call, along with René Girard, the “Romantic Lie.” The French title of Girard’s first book, Deceit, Desire, and the Novel is actually Mensonge Romantique et Vérité Romanesque, i.e., Romantic Lying and Novelistic Truth. In this book Girard tracks the way that protagonists from the novels of Cervantes, Stendhal, Dostoevsky, and Proust pursue apparently ‘authentic’ desires. To take the example of Don Quixote: Quixote mistakenly believes his obsession with Chivalry to be natural and beautiful, rather than an ill-fated idea that was put in his head by books he read. By the end of the tale the Reality Principle has given him his comeuppance, and he has renounced chivalry.

The protagonists of Stendhal, Dostoevsky, and Proust are all the more ill-fated because their desires are generated not by outdated texts but by the living people around them. Each of these protagonists assumes himself an authentic Romantic Hero in a world full of other people imagining themselves authentic Romantic Heroes, while in the end all these people are doing is imitating one another. For Girard, the great achievement of the mid- to late 19th century realist novel is that it shows the vanity of early 19th century Romanticism: The novel demonstrates that the hero’s desire is mediated by his culture. Whatever greatness the Romantic poet had was not graspable by Romantic himself.

Are we not, as a race, collectively coming to such a realization about ourselves today? Our collective Romantic Lie is that human beings are autonomous, rational subjects who are in and of themselves vastly important and interesting. The novelistic truth is that we are important only as sporadically useful vessels of the divine. That this is the most important element of humanity is a fact stated with violent emphasis by every culture that has ever existed. It is only ours which denies it. This notion has been forgotten for the last 300 years or so, which is not very long in the grand scheme of things. And it appears that this centuries-long stupor will be lifted not by the glorious appearance of any god, but by the unavoidable knowledge human stupidity. Atheism shall be felled by a meme: the NPC.

The NPC-like nature of humanity shows us that humans qua humans have very little to be proud of. It is only as individuals, touched at individual moments by the divine spark, that we may be worthy of the belief that we ought to exist. What this actually means is a matter of theology, or at least phenomenology, and will have to be left for another poast.

But for now we can say that while the saturation of the physical world with the digital world is painful—not only for Romantics, but for nearly everyone who is not prepared to sacrifice himself to whatever shall emerge from this new world being born—it is, overall, good for us. It is directionally correct in the way that it steers humankind away from our Romantic/modernist notions of ourselves. It is a slice of humble pie we can eat either freshly baked or rotten, but we’ll have to eat it at some point.

The challenge is to carry this new knowledge with us without being completely flattened by it. After I’d left that museum in Lisbon, I walked around aimlessly until I saw a cab to hail. On the way to the airport I had a long conversation with the driver. He told me that his wife got very ill and the government only gave her 300 Euro a month, while those who had recently arrived to the country from countries such as Brazil got 500 Euro a month to do absolutely nothing. The driver felt very angry about this. He told me that we worked twelve to fourteen hours a day to provide for his young children and did not find it fair that the government was what I suppose my communist friends would call a petit bourgeois or a kulak. (I’m not quite up on the current terminology.) But he was a very nice man with a winning smile and, it seemed to me, some thoughtful points, and I hope he will not be liquidated. I also realized that if I had hailed him with Uber, we likely would not have been having this conversation. He would have been too worried about potential blowback of his speech, and about receiving fewer than five stars.

Our ability to take in arbitrarily large amounts of information in the digital age will lead us to insights our ancestors could only have dreamed of. But we also don’t want arbitrarily large sections of what we do broadcast to everyone. That sounds paradoxical but is technically possible. The amount of information that other people choose to share will still be larger than the amount of information we’re all able to take in. If everyone shares what he or she wishes to share, that’s still more than enough. We can, hypothetically, have the benefits of a global digital network without its worst downsides. But to do that we’re going to have to become discerning about which technologies we use and how we use them. If we can accept what the digital network reveals to us without going mad, a new stage of human evolution may be revealed to us. But that’s for another time. . . .

As Schmitt pointed out, the discussion of ‘Romanticism’ is itself usually ‘Romantic.’ Very hard to recognize much of what the actual Romantics said and thought in this kind of account. Girard is a worthy thinker but is hardly a reliable source on the thought of others.